FACT: Three people die each year testing if a 9V battery works on their tongue.

FACT: Total asphyxiations attributed to rice cake eating since 1965: 1,601.

– FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: Non-dairy creamer is flammable.

FACT: Poets have a life span fifteen years below average.

– FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: More people are killed annually by donkeys than die in air crashes.

FACT: Deaths attributed to “loud sounds” since 1970: 34,831.

- FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: Since 2001, 987 children have been killed while buying ice cream.

– FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: Halogen floor lamps caused approximately 270 fires and 19 deaths per year.

– FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: Nutmeg is extremely poisonous if injected intravenously.

FACT: One of the largest carriers of hepatitis B is dinner mints.

FACT: 99% of all "mazes" can be solved if you walk to the right every time you have to choose between left and right.

FACT: In 2003, 24 people died from inhaling popcorn fumes.

– FINAL EXITS by Michael Largo

FACT: A group of unicorns is called a blessing.

The Unicorn Question

From the archive...

We were just arriving home from the park, when my daughter sprung the question. She was on her bike. I was on foot. It was a beautiful day, though overcast, and the park had been muddy, and she was a little tired from the bike ride home. She'd been quiet the last half-block. I blamed it on muscle fatigue. It turns out she was mulling the nature of reality.

"Can we go to the jungle and see unicorns?" she asked. She said it casually, as if she were asking to go to the zoo and see elephants.

My daughter is approaching 4, and we expect these big questions every now and again. We'd watched "The Adventures of Robin Hood" with Errol Flynn and had an exhaustive discussion as to why Prince John could be a bad guy when he seemed so nice. ("But he's a prince," she kept saying, "and happy.")

But I was not prepared for The Unicorn Question.

I decided to attempt a sidestep.

"Unicorns don't live in the jungle," I said.

My daughter pushed her bike up the grass hill to our yard. "Where do they live?" she asked.

This stumped me. "Um, meadows?" I said.

She turned back and squinted at me, clearly dubious. "Meadows?"

"The old English countryside?" I guessed.

She wasn't buying it. "Where do unicorns really live?" she asked.

I had to come clean. "In a magic land," I said.

She frowned. "Can we go there?"

I forced a big excited, fake smile. "That's the great thing about magic lands, you can go any time you want, because they exist in your imagination," I said.

She stood in the yard, her pink bike helmet strapped under her chin, and looked at me the way she sometimes looks at her father. "Are unicorns real?" she asked.

There it was.

What was I supposed to do? Lie? It was a direct question. "They're imaginary," I said, immediately feeling like a jerk.

"Like dinosaurs?" she asked.

"Dinosaurs used to be real," I said. "They lived a long, long time ago. Unicorns are made up."

Her mouth tightened for a moment, and then she turned back toward the house and started to walk her bike toward the porch. "OK," she said.

I felt like a monster. I had destroyed her belief in unicorns. I was a unicorn murderer. I imagined piles of unicorn carcasses, their horns snapped off, their white coats matted with blood.

We went inside and sat down with my husband.

"I don't see the moon," my daughter said to him. (It was mid-afternoon, and the sky was entirely blanketed with clouds.)

"It's on the other side of the world," my husband said.

"No it's not," she said. She peered out the French doors to the backyard. "It's out there." In her defense, we had seen the moon in the daytime sky a few weeks earlier.

"It's too cloudy," I said.

"It's on the other side of the world," my husband said again. Sometimes he thinks we ignore him.

She craned her neck so she could see more sky. "I can't find it," my daughter said.

"Trust me," my husband said.

My daughter crossed her arms. "I want to see the moon," she said.

My husband reached for her toy phone, which was sitting on the coffee table.

"Hello?" he said into it. "Is this the moon?" He paused. "Where are you now?" He listened and nodded and then looked over at our daughter. "Oh, the other side of the world?" He paused. "Would you mind telling my daughter that?" He held the phone out to her. "The moon wants to talk to you," he said.

She took the phone and held it to her ear. "Hello, Moon," she said. She listened for a moment. "OK," she said. "I understand. Goodbye." She lowered the phone and turned back to my husband. "The moon says that it is half up today," she said. "And that you are wrong."

Her imagination was intact, unicorn massacre notwithstanding.

- Chelsea's blog

- Login to post comments

Recent Posts

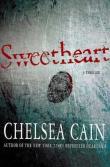

- Heartsick named in the top 6 serial killer books by S.A. Cosby in the NYT

- Fancy French-y retreat in Collioure, France

- Last Minute Zoom Writing Hootenannies

- Book Riot names HEARTSICK one of the Top Ten Mystery Books Set in the Pacific Northwest

- Chelsea's Law & Order SVU drinking game

- It's not about the moths.

- I Don't Want to Lose

- I Don't Want to Lose

- Want to go on vacation with me?

- Wave!

Archive

- September 2018 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- January 2019 (2)

- April 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- August 2019 (2)

- January 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

Chelsea Cain | Website by Dorey Design Group